Zuzmann (to the left) with his flying circus after the war.

Since Flik 20 had at least two Slovenes serving in the unit, let us focus a bit more on this particular unit. It was established in January of February of 1916 and almost immediately deployed to Vladimir-Volinsky in the north-western parts of today's Ukraine, also known as Volhynia. Flik 20 was commanded by a Captain Jenő Czapáry, and the unit was equipped with both Knoller-Albatros B.I two-seaters and probably later Hansa-Brandenburg C.I.

The most famous aviator of Flik 20 was Oberleutnant Kurt Nachod (1890-1918), who was the first Austrian to achieve five victories as an observer, and he shared two victories, a Farman on May 31, 1916, which was forced to land near Klewan, and another Farman on July 3, 1916, just north of Luck. The latter aircraft was sighted below Nachod and Zuzmann, and Nachod ordered Zuzmann to dive towards the Farman (the observer actually commanded the aircraft in the Austro-Hungarian and German air forces). However, Nachod's machine gun jammed, but he produced a carbine, and his fire was accurate enough to force even this Russian Farman to land. On both occasions, Nachod flew as an observer in Knoller-Albatros B.I 22.18, which was piloted by Zuzmann on at least July 3. Following a long career as an observer, Nachod did get a pilot's license, but he was badly injured after crashing while night flying on May 9, 1918. Nachod died of his injuries two days later.

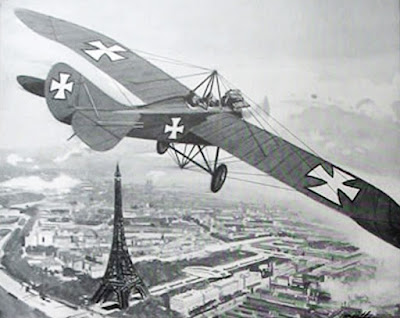

Knoller-Albatros C.I

Zuzmann survived the war, and he participated in flying aircraft, amongst them a Albatros D.II, from parts of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire to Czechoslovakia where they were sold to the armed forces. He was also engaged in a flying cirkus. Zuzmann also opened a private airfield in 1930 after acquiring a 30-year lease on the Voeslau/Kottingbrunn airfield, some miles south of Wien-Aspern. The airfield was taken over by the German Luftwaffe after the annexation of Austria in 1938 and renamed Fliegerhorst Voeslau.

Kurt Nachod

Sources:

http://aces.safarikovi.org/victories/slovenia-ww1.html

http://www.airports-worldwide.com/austria/voeslau_austria.htm

http://www.feudal.cz/html/franz_zuzmann.htm

Chris Chant. Austro-Hungarian Aces of World War 1. Osprey, 2002

Jon Guttman. Reconnaissance and Bomber Aces of World War 1. Osprey,

Dr. Csonkaréti Károly: A császári és királyi légierő

Justin D. Murphy. Military Aircraft, O,rigins to 1918. ABC-CLIO, 2005

Dr. Csonkaréti Károly: A császári és királyi légierő

Justin D. Murphy. Military Aircraft, O,rigins to 1918. ABC-CLIO, 2005

Dr. Martin O'Connor. Air Aces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire 1914-1918. Flying Machines Press, 1986